Blog

Trusted source, trusted information, trusted support: The role of trust in resident emergency response

Post copied from SFPE Europe magazine.

If you were to ask people about their ideal, best case scenario response of people in a building fire, it might be something akin to everyone in the building instantly becoming aware of the fire, immediately following the fire safety guidance for their building, and ultimately everyone coming out of the incident unscathed because the correct procedures were followed.

This article lays out some of the reasons why people may not react this way. We show that trust is critical to understanding why people may delay response to a threat, and crucially why they might not follow the safety guidance.

First, let us look at computational models that simulate how people react in emergencies. Envisioning how people respond to fires is a basis for these models. Three crucial estimates of these models are the time taken for people to become aware of a threat, the time taken before starting to make their way to a safe space, and their likely behaviours as they progress through the emergency. Computational models set these estimates based on assumptions of how people will react, such as people’s awareness of threat taking anything from one second to several hours

Here is the crux. Some models are based on assumptions made from analysing footage of emergencies and inferring what happened. Other models are based on survey data from people who experienced previous emergencies. A not insubstantial number of models include the creator’s presumptions of how people might pay attention to threats and act.

The reason that assumptions are currently used is partially because it is difficult to gather knowledge about people’s perceptions and decision-making in real-time during an emergency. Research from social psychology has made great strides in understanding people’s behaviour in emergencies after the incidents (e.g., [1,2]). However, researchers cannot magically appear at an emergency with a clipboard and voice recorder to ask people why they are acting the way they do. Even having video footage of an incident does not allow the researcher to ask the participants in real time what they were paying attention to and why they chose certain decisions. Yet, the lack of nuanced data into people’s perceptions and decision-making in emergencies does mean that many computational models – despite best efforts - are based on limited understanding of how people respond in emergencies.

In recent research we set out to explore how, why and when people respond in the immediate moments of an emergency, with a focus on the experiences of residents of high-rise residential buildings in the UK. We conducted surveys [3] and focus group interviews [4] with residents to better understand how, why and when they would react when first alerted to a potential threat. We found that that trust is pivotal to residents’ responses and many of the assumptions used in models, and in broader emergency preparedness and response, need re-evaluation.

The surveys were used to ask residents how clear they found the fire safety guidance for their building, their trust in the guidance, their trust in the creators of the guidance, and how willing they were to follow the guidance. When we analysed views of the guidance to stay put, we found that having clear guidance was not related to residents’ willingness to follow it. Instead, willingness to follow the guidance was related to their trust in the guidance and their trust in the guidance creators. When looking at the guidance to evacuate, clear guidance was related to willingness to follow it. However, trust in the guidance and trust in the creators of the guidance were both still important parts of the picture of overall willingness to follow the guidance.

Another important piece of the puzzle was residents’ trust that their building was safely equipped to have an evacuation or stay put policy in place. When considering both the guidance to stay put and evacuate, residents’ trust that their building was sufficiently safely equipped was significantly correlated with how much they trusted the guidance and creators of the guidance.

The focus group interviews shed more light on why trust is such an important factor in emergency response. Residents reported that they distrusted people or organisations who they felt were not acting on their behalf. For example, they found it difficult to trust information from local authorities or landlords who had previously acted in ways that did not support the residents. Some residents said they put safety guidance directly into the bin if they had sour relations with the providers. On the other hand, most residents said they would follow guidance from organisations such as the fire and rescue services specifically because their purpose is to keep them safe.

Trust among residents was also key to understanding how, why, and when residents reacted to previous fires and potential fire incidents in their building. Residents reported that they would seek and share information about the incident with trusted residents if they were unsure about the situation. They would then discuss the extent of the threat, possible actions, and decide how to respond. This was primarily in person, but residents also shared information on social media and through phone messaging applications. Importantly, they did not just look to the actions of nearby neighbours when deciding how to respond. Instead, residents sought out others who they were already part of a group with, because of shared issues in the building, or who they saw as friends. They also expected that there would be support from the other residents (such as being told about the fire) if they knew other residents or felt there was a positive community atmosphere in the building.

Together, our surveys and focus group interviews show that we need to include the importance of trust in computational models and emergency planning. We need to incorporate how trust – and specifically the importance of being part of a group with others - affects how, why and when people respond to fire incidents. Making fire safety guidance clear is not sufficient: the people creating it need to work to be trusted by residents, including by addressing their needs so that trust in the guidance itself can be developed. We cannot assume that people will immediately react to a fire because our work shows that residents might expect others they trust to alert them if an incident is real and dangerous. Related to this, delays may occur prior to evacuation or movement to a safe place because residents seek and share information with others in their building, move around the building to do this, and use multiple methods to communicate with others.

An outcome of the research suggests that if we do not update our models and guidance to include the role of trust then we risk missing important reasons for reactions to fire incidents. If we neglect the role of trust then we risk not understanding why the ideal, best case scenario pictured at the start of this article is unlikely to happen.

Funding: This article is based on research commissioned as part of a technical review of Approved Document B being undertaken by the Department of Levelling Up, Housing and Communities.

References

[1] Drury, J., Carter, H., Cocking, C., Ntontis, E., Tekin Guven, S., Amlôt, R., (2019). Facilitating collective psychosocial resilience in the public in emergencies: Twelve recommendations based on the social identity approach. Frontiers in Public Health, 7 (141), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00141

[2] Drury, J., Cocking, C., & Reicher, S. D. (2009). Everyone for themselves? A comparative study of crowd solidarity among emergency survivors. British Journal of Social Psychology, 48(3), 487-506. http://dx.doi.org/10.1348/014466608X357893

[3] Templeton, A., Nash, C., Spearpoint, M., Gwynne, S., Hui, X., & Arnott, M. (2023). Who and what is trusted in fire incidents? The role of trust in guidance and guidance creators in resident response to fire incidents in high-rise residential buildings. Safety Science, 164, e106172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2023.106172

[4] Templeton, A., Nash, C., Lewis, L., Gwynne, S., Spearpoint, M. (2023). Information sharing and support among residents in response to fire incidents in high-rise residential buildings. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 92, e103713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2023.103713

Identity leadership and adherence to COVID-19 guidance within hospital settings

By Kayleigh Smith - 19.01.23

The NHS was at the core of the pandemic response, with both frontline staff and leadership facing significant challenges throughout. Staff shortages due to COVID-19 put substantial strain on resources, particularly in frontline hospital settings where the risk of staff contracting the disease is increased through contact with infected patients and other healthcare workers. Crucially, a quick succession of new evidence about how to mitigate COVID-19 spread meant that hospital leadership had to rapidly communicate with frontline staff to ensure they were following the newest guidance. We aimed to understand the role of leadership – particularly the role of identity leadership – in promoting staff adherence to the COVID-19 safety guidance with NHS hospitals in Scotland.

The social identity approach to leadership (also referred to as identity leadership; Haslam et al., 2020) proposes that leaders can be viewed positively and promote engagement in safe behaviour by working within the group rather than authoritatively towards or at a social group (such as towards frontline NHS staff). We were particularly interested in two aspects of identity leadership in this study – identity prototypicality and identity advancement.

Identity prototypical leaders are those who represent what it means to be ‘one of us’, i.e., an ideal member of the group (Hogg, 2001). Identity advancing leaders are those who are seen to be standing for the group and are viewed as getting things done on behalf of the group (Haslam et al., 2020; Steffens et al., 2014).

Leaders who are seen as either identity prototypical or identity advancing tend to be viewed positively by group members – such as being rated as more effective (Steffens et al., 2013), endorsed (Graf et al., 2012), and gaining greater feelings of trust from group members (Barreto & Hogg, 2017). Not only are these leaders rated more positively, but they can also promote engagement in safe behaviour (via increased group trust, e.g., Clark et al., 2020) and group followership (such as voting for these leaders, e.g., Steffens et al., 2016).

Through our research, we wanted to find out whether staff discussed hospital leaders in relation to identity prototypicality and/or identity advancement, and whether identity leadership (or a lack of identity leadership) related to staff’s self-reported adherence and attitudes to the COVID-19 safety guidance.

We conducted 25 interviews with staff across two NHS Scotland hospitals. Through our analysis we found two themes within our research: 1) the importance of present leaders who do the same tasks as frontline staff, and 2) approachable leaders who act on the concerns of staff.

We found that leaders who were present on the wards and engaged in the same tasks as frontline staff – leaders who demonstrated ‘prototypical’ group membership - were viewed more positively than non-present leaders who were seen to be distant and far away in their ‘ivory towers’. Present leaders were also seen to promote the ability for NHS staff to adhere to safety guidelines. They did so as their presence allowed them to understand what it was like working on the individual wards, what the environments contained, and therefore were able to provide guidance that was practical and applicable to that specific environment. In comparison, guidance from non-present leaders, particularly those who were believed to have ‘never actually done the job’, was seen as impractical and ‘very irrelevant from what’s going on on the ground’ which limited staff’s ability to adhere to it even if they wanted to.

We also found that leaders who were approachable and acted on the concerns raised by staff – those leaders who demonstrated identity advancement – were viewed more positively compared to leaders who were seen as unapproachable or who were not acting on the concerns of staff. We found that these approachable leaders promoted adherence by providing opportunities for staff to clarify the guidance itself, where the clarity of guidance – if it was ‘clear cut… if it was very linear and easy to understand’ - was key to allowing staff to adhere. Additionally, leaders who acted on the concerns of staff were able to update the safety guidance in line with the requirements of frontline staff, providing the opportunity and ability for staff to adhere to the safety guidance. On the other hand, when staff felt leaders were not acting on their concerns – such as being seen to be dismissing PPE concerns as something that ‘everybody’s having trouble with’ – staff felt this limited their ability to do their job safely. As one of the interviewees highlighted - ‘if we don’t have the right PPE to be able to surgeries safely then we can’t do our surgeries’.

Overall, our research highlights that leaders can encourage safe behaviour by providing the opportunity and ability for staff to adhere to guidance. By understanding what contributes to positive relations with leaders and how leaders can contribute to safety, NHS leadership training can be further improved to promote positive staff-leadership relationships and support the creation of guidance that allows staff to engage in safe behaviour within healthcare settings. We are working on that at the moment, so watch this space!

How can we facilitate coordination between emergency responders and the public in emergencies, and where are the challenges?

By Sayaka Hinata - 19.12.2022

On the night of 29 October 2022, a crowd crush occurred during Halloween events in the Itaewon neighbourhood of Seoul, South Korea, killing at least 156 people died. The recurrence of casualties in crowds – either in planned events or sudden onset emergencies - show that more work is needed to effectively plan and respond to emergencies.

Emergency management can substantially mitigate loss of live if effective planning and response is in place. However, a core component to mitigating this damage is understanding how and why the public respond to risk communication from emergency responders. Research from crowd psychology has thoroughly researched how and why members of the public respond in emergencies. So how can this knowledge be used to improve current emergency management and prevent these damages in the future?

There has been over 40 years of research and recommendations on best practices for risk communication (Boholm, 2019) yet many gaps need addressed. For example, risk communication from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency was ineffective in building trust and overcoming conflict during an argument over contaminated land in Aspen, Colorado, even though their approach was based on an article stating seven rules of risk communication (Stratman et al, 1995) . Research by Kasperson (2014) suggested that there has been little improvement in risk communication practices because of the significant gap between the recommendations derived from researching risk communication and the practice of emergency responders and government agencies.

Research from crowd psychology suggests ways that communication from emergency responders can be developed, and ways to improve coordination with the public. Notably, Drury et al. (2019) provide twelve recommendations to improve resilience in emergencies. In this blog post, I focus on three of those recommendations that are most related to my PhD research into understanding emergency responder communication strategies.

The first recommendation is to build positive social connections between members of the public and emergency responders and government agencies by providing information to the public. In emergencies, people seek practical information to make informed decisions. Gaining information about the situation can help to reduce uncertainty and therefore stress about the situation. Providing information in the form of updates can also facilitate relationship-building between emergency responders and the public under time-pressure in the response phases of emergencies. Emergency responders should show respect for the public by listening to the public’s needs, being open and honest, explaining the reasons why the procedure is necessary, and providing sufficient practical information about how to respond (Carter et al., 2015). Further, emergency responders should provide information to the public as soon as possible, and continue updating the public when they have new information.

Second, emergency responders should accommodate the public urge to help others. Emergency responders often cannot reach affected people in time (such as due to needing to establish areas are safe) but the public can be remarkably proactive and resilient during this time. In emergencies, survivors can become “zero responders” where they are the first on the scene to provide help. Frequently in emergencies, people come together as a group due to the shared experience or threat and provide help to others on the basis of that group membership. The public may want to help supporting others, reporting the event, engaging in reconnaissance, and even assistance with triage (Adini, 2012) despite not having expertise.

Third, emergency responders should use shared language and instructions to facilitate the feeling that the public and the professional responders are part of the same group. Research suggests that the public may unite as a group in an emergency, but professional emergency responders may unintentionally prevent this process if they take a 'command and control’ approach. This authoritative approach can cause disconnect with the public and therefore resistance. Instead, emergency responders should, to produce or expand the connection with the public by using collective terms such as “us” and “we” (rather than “you”) when speaking to members of the public, and directing them to common goals such as shared safety.

In conclusion, in terms of effective risk communication with members of the public in emergencies, emergency responders and government agencies can consider three these recommendations from crowd psychology. However, practical and operational barriers may make it difficult for emergency services to fully put the recommendations into practice. For example, Palttala et al (2011) show that emergency responders and government agencies face the challenge that they are obligated to give information as quickly as possible, but not at the expense of accuracy and liability in crisis situations. This, alongside confidentiality considerations (e.g., injuries sustained) may make it difficult to meet the public’s requirement of getting timely and open information. Similarly, the environment in an emergency may make it difficult for emergency responders to enlist the help of the public, such as if they experience a physical barrier or can only rely on one-way communication (e.g., loudspeaker) with the public.

Therefore, my PhD research aims to address what the barriers are that stop emergency responders and government agencies from 1) prioritising informative and actionable risk and crisis communication and 2) accommodating the public urge to help (e.g., by sharing information). I strongly hope my research will make a bridge between crowd psychology and emergency management further to improve safety in emergencies.

Social identity processes in response to fire incidents in high-rise residential buildings

By Layla Lewis and Lisa Li

High-rise buildings are being turned into luxury apartments, studios, and penthouses with more than 525 buildings over 20 storeys high being built during 2020, and a further 89 high-rises already in progress. More so, 88% of high-rises in 2019 contained residential spaces compared to only 14% in 2010 (Craggs, 2018). Yet many are wary of this sharp incline with the memory of the Grenfell Tower tragedy still fresh in mind.

The regulation of high-rise buildings as well as how fire safety guidance is distributed to residents has been in question. The public inquiry into the Grenfell Tower fire and the circumstances surrounding the event has raised concerns regarding “stay put” fire safety legislation and residents’ ability to follow it, making the recommendation that “fire and rescue services develop policies for partial and total evacuation of high-rise residential buildings and training to support them”. The tragedy of Grenfell has cast a sharp light on the need for better fire safety strategies. However, a crucial missing component of fire safety strategies is understanding how and why people in high-rise buildings may respond to a fire incident, and what influences the extent to which they follow the guidance in place.

Research using the Social Identity Approach (Reicher et al., 2010) shows how group processes can impact response to fire incidents. From a social psychological perceptive, emergencies can induce a sense of shared social identity by creating feelings of common fate during the threat. The perception of a shared social identity can give rise to feelings of solidarity in adverse events, which serves as the basis for offering and expecting help and support from other ingroup members (e.g., Drury et al., 2009).

The impact of group processes on behaviour can be found in multiple types of emergencies. For example, by increasing social support among those facing the emergency (Levine et al., 2005), and being more likely to follow guidance from people seen as being in the same social group (Carter et al., 2013). Research by Drury et al. (2009) with survivors of the July 7th London bombings illustrates a clear example of collective behaviour within an emergency evacuation. Many viewed themselves as part of a group with the other survivors and it was noted that people cooperated and coordinated their efforts to get all to safety on the basis of the shared group membership. Moreover, individuals stayed behind to help others they had no prior relation to regardless of the risk to themselves because they saw them as being part of the same social group.

A successful fire evacuation usually requires evacuees to follow fire safety guidance quickly, because delays may lead to irredeemably fatal consequences considering the overwhelming speed at which fires can spread. Importantly, a person’s decision on whether to evacuate, their route choice, and whose information they attend to can largely depend on what actions evacuees perceive others in their group are taking (Bode et al., 2015). For example, instead of evacuating immediately, people may seek additional information from others and search for others with whom they share pre-existing social bonds (Sime, 1983). Hence, there is a need to understand the potential impacts of any group processes, including group norms, group relationships and social identities, on individual fire evacuation performance. Despite this, there has been very little research into the group processes present when evacuating high-rise residential buildings in the event of a fire.

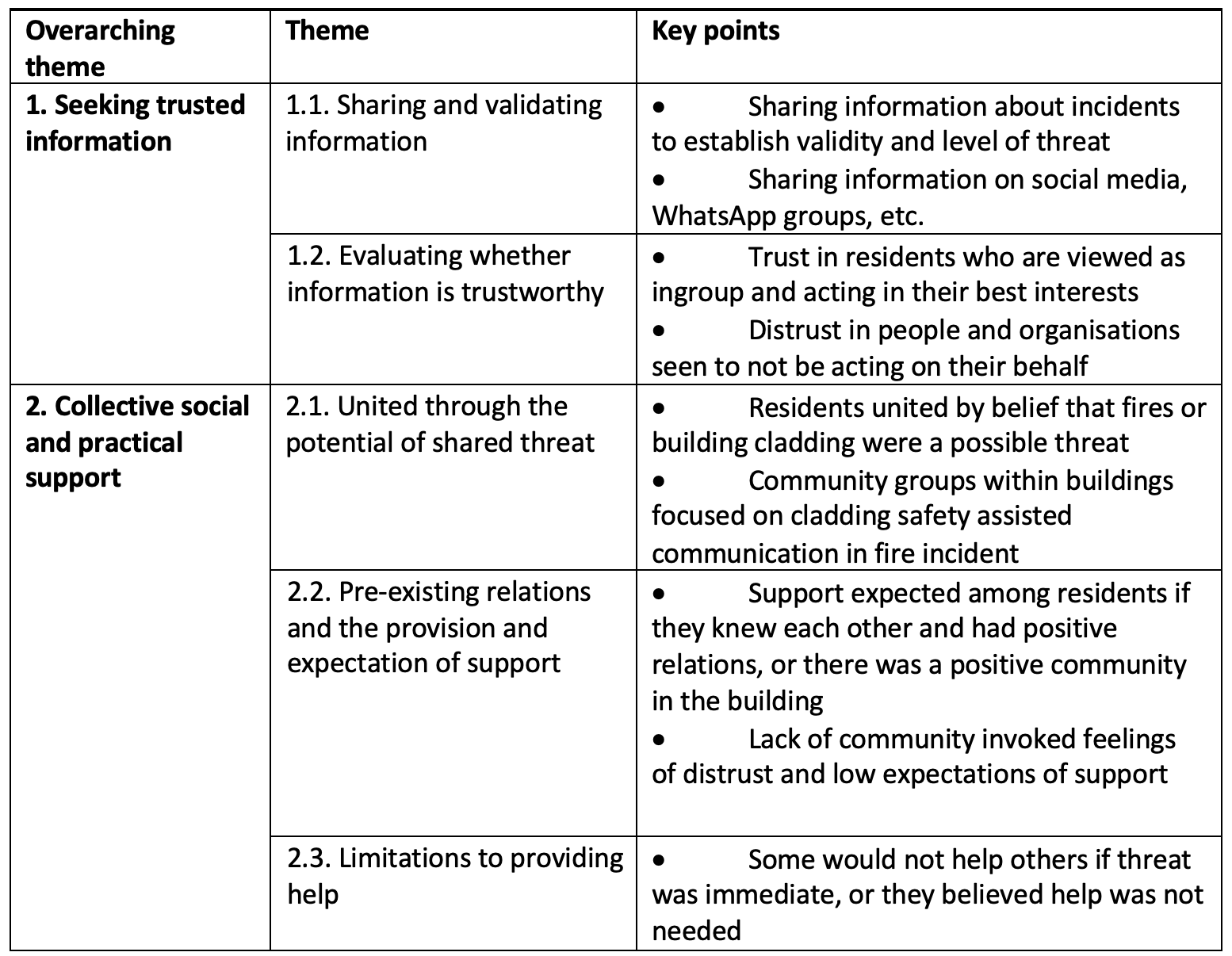

Our projects aimed to address this gap by investigating group processes within the context of residential high-rise buildings in evacuations, with a particular focus on pre-existing social bonds and social influence in decision-making. We analysed interviews with 40 high-rise building residents through the lens of the Social Identity Approach to examine residents’ views of what factors either impacted their perceptions, decision-making and actions during a previous fire incident, or would impact them in the event of a fire in their building.

A recurring theme among the participants was the provision and expectation of help and support in an emergency. Fire incidents were viewed as a common threat to the safety of all residents, and this created a context for residents to develop shared community identity. Under these circumstances, residents reported being willing to offer help and support to other residents, and they often expected other residents to offer help to them. For example, some residents expressed deep concern for the safety of their neighbours, and said they would notify others about the fire by knocking on neighbours’ doors and making them aware of the danger before evacuating, as well as helping others to evacuate.

Our interviews also found that perceiving others to be in the same social group resulted in individuals seeking validation about what was happening with the fire. Social media groups (e.g., WhatsApp, Facebook) were commonly used to coordinate and communicate information during fire emergencies and were viewed as quite a reliable source of information.

Although helping behaviours and information sharing between residents in emergencies reflects community cohesion and solidarity, a potentially unintended consequence could be delayed evacuation. For instance, alerting other residents by knocking neighbours’ doors can be helpful in terms of informing more residents about the fire incident and potentially increasing the number of people who evacuate. However, it risks personal safety by delaying a person’s evacuation, and may impede fire and rescue service operations if a blockage occurs.

Overall, the findings from our research suggest that group processes are commonly observed during fire incidents and would also be important in future incidents. Therefore, it is vital for fire and other emergency service planners to understand group processes in responses to fire incidents. In particular, they should attend to how residents may look to members of their group for information about the emergency, seek others in the building to share information, and account for the likelihood that residents will collectively coordinate to help others.